Inflation: Solution or Problem?

My framework of thinking around inflation (research in progress)

Disclaimer: I don’t consider myself an expert on the topic of inflation so this is more of an OP-ed than an analytical note.

Inflation is a hot topic lately and rightfully so. A lot of different views and various takes circulating around but the latest comment by Canada’s Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland was one of the red flags for me so I decided to share my views regarding inflation and related topics.

Before explaining why it’s a red flag I’d like to start with my overall framework for inflation. Like with many other things inflation is ultimately shaped by every one of us. Our purchase decisions lead to the formation of the demand for goods and services and decisions of producers of those goods and services lead to supply formation. The resulting balance between those two defines where prices go. Year-over-year prices increase is called inflation.

Since inflation is shaped by every one of us it’s extremely difficult to predict it, that’s why the Bank of Canada has significantly fallen short while trying to forecast it lately (link). It’s much easier to do during the normal times though and the Bank of Canada has a pretty good track record of doing it.

Central Banks and governments are trying to impact inflation by monetary and fiscal policies but that just provides incentives to the market, they can’t force people to spend or manufacturers to produce.

That’s why Tiff Macklem, Governor of the Bank of Canada is reassuring the market that current inflation is transitory in pretty much every interview. Regardless of whether he believes it or not he needs to convince the market which will lead to the desired outcome - inflation easing. Persistent inflation moving to a higher level would be undesirable since it’s not currently allowed by their mandate.

Sustainable inflation levels

2% inflation is just a number selected by economists and central banks are shaping their actions around achieving this target. There is a set of parameters where the economy can sustainably function with inflation being 2%. For example, some of those parameters may include wage growth being 2%, GDP growth 2%, and 10y bond yield being 3%.

A similar set of parameters can be calculated for inflation 3%, 4%, 5% etc. It’s important to understand that every such level will be theoretically sustainable. A good analogy would be transmission gears in a car. Additionally, the level can be 1% or 0% where Japan is right now.

This set of parameters is unique for every inflation level in order to be theoretically sustainable so when people are saying “Government will just let inflation run hot while keeping bond yields low in order to devalue debt pile” - the questions they should ask themselves: “Is it really a set of parameters which can sustainably exist for an extended period of time?”, “Who will be losing money in such an environment?”, “Will they do anything about it and what it will likely be?”.

During the 60-70s inflation was trending higher for more than a decade in the US so potentially it can move to a higher level again.

However, today’s mandate prohibits persistent inflation growth above 3% so central banks must timely prevent any persistent inflation buildup above 2% or adjust their mandate.

A 10-year breakeven inflation rate above 3% would indicate to me that the market lost trust in FED’s ability to control inflation. Central Bankers are watching this indicator very closely and seem to be ready to switch to a more hawkish stance in order to bring future inflation expectations down and maintain trust.

Can we trust official inflation metrics?

There are a lot of debates on that topic and I don’t want to participate in those. There is likely something to it when so many people believe that Central Banks are underestimating inflation however on the other hand I’m seeing a ton of posts supported by cherry-picked examples of how things are getting more expensive. At the same time there is exactly zero posts in my timeline highlighting how you are getting double the size of TV and 4K as well for the same price you paid for a small HD TV in the past, how many features new cars are getting, and how rent becomes cheaper during pandemic due to work from home expenses tax claims.

Someone posted a picture of a very expensive steak recently but nobody is posting this:

It seems that there are definitely some psychological factors in play that make us focus more on things getting more expensive vs things getting less expensive or better for the same price leading to biased perception of inflation.

I’m not trying to say CPI is accurately reflects reality, I tend to agree that it may be underestimating price pressures, but I do see evidences of bias and don’t think the error is big enough to say CPI is not trusted.

At the end of the day, until someone comes up with a more accurate measure of inflation that would be widely adopted, everyone has to stick to the official CPI.

Bank of Canada is already behind the inflation curve

Managing inflation by monetary policy is a forward-looking process that takes time. Bank of Canada estimates that full effect of monetary policy adjustment to be achieved in 6-8 quarters. (7 on average)

Now let’s check their own latest inflation forecast. The output gap is expected to be closed in Q4 2022 with persistent inflationary pressures starting to build up after that.

Traditionally, Central Bank would proactively react to those pressures and adjust monetary policy (raise interest rates). Since monetary policy adjustment takes 7 quarters on average to achieve full impact, let’s subtract 7 quarters from Q1 2023. That will lead us to Q2 2021, a time when the Bank of Canada was supposed to raise interest rates based on its own framework and projections.

Why didn’t they do it? I think there are several reasons here. Some of those are:

We are still in the midst of the pandemic;

There are a lot of uncertainties so it is better to have an easier monetary policy just in case than a tighter one;

Inflation overshoot is the new trend in central banking globally;

Maybe even a little bit of embarrassment after the Bank of Canada promised that rates are going to stay low for a very long time. Imagine raising the interest rate the next year after you say that?

So the Bank of Canada is intentionally delaying rate hikes and creating a modest inflation overshoot in 2023 (see the chart above and also confirmed during the speeches). They hope it produces better overall results (study). Just to clarify, overshoot is not 5% or 10%, overshoot is 0.5% for a total of 2.5% inflation by the end of 2023.

This experiment comes with great risk. If persistent inflation turns out to be higher than central bankers currently forecasting it, they will end up in a tough spot since monetary policy adjustments take effect with a big lag and they are already behind the inflation curve.

The possible action in this scenario would be a rapid increase of the interest rates as an attempt to have a sooner influence on the economy and cooling of inflationary pressures.

What is the risk of higher persistent inflation?

If the economy can sustainably function with 3% persistent inflation what is the risk here? The risk is related to the valuation of asset classes. A higher inflation level will require higher bond yields (investors need to make money after all). Higher bond yields in turn lead to lower asset prices.

Here is how it works: If you had an investment during the 2% inflation era with a 3% return, now in the 3% era new investors will only be interested in opportunities with a 4% return. In order to turn your 3% return investment into a 4% one, you need to sell it at a 25% discount (all else being equal). This is a theoretical exercise, nothing in the real world works strictly according to fundamentals.

This math works similarly for any cash-flowing investment such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and others. That’s why it’s so important for central bankers to return inflation back to 2%.

Why Central Bank can’t just always buy more bonds (QE) to bring yields down?

Let’s say we are in a situation when the economy is running at its full potential, inflation and wage growth are persistently 3%, and bond yields are heading towards 4%.

Since the economy is running at its full potential bond purchases with newly created money (QE) will stimulate the economy further leading to higher inflationary pressures. QE is useful when the economy is distressed and needs stimulus but it will add fuel to the fire when the economy already runs hot.

Plus, it will send a signal to bondholders that further losses are ahead since real yields become even more negative. Private capital will leave the bond market, potentially adding more to inflationary pressures.

There are tactics available for the government to keep yields pinned down such as Yield Curve Control (YCC), however, with negative real yields, they will likely need to force the private sector (usually banks and pension funds) to hold bonds to make it somewhat sustainable. That tactic was implemented in the 1940s and some people believe it will be implemented again but so far there is zero indication from policymakers.

Negative real yield. Is it a problem or not?

Negative real(adjusted for inflation) yields became the norm in recent years with the pile of negative-yielding debt growing substantially globally.

I don’t believe it’s fundamentally sustainable. Investment should generate profit without speculative expectations regarding future valuation.

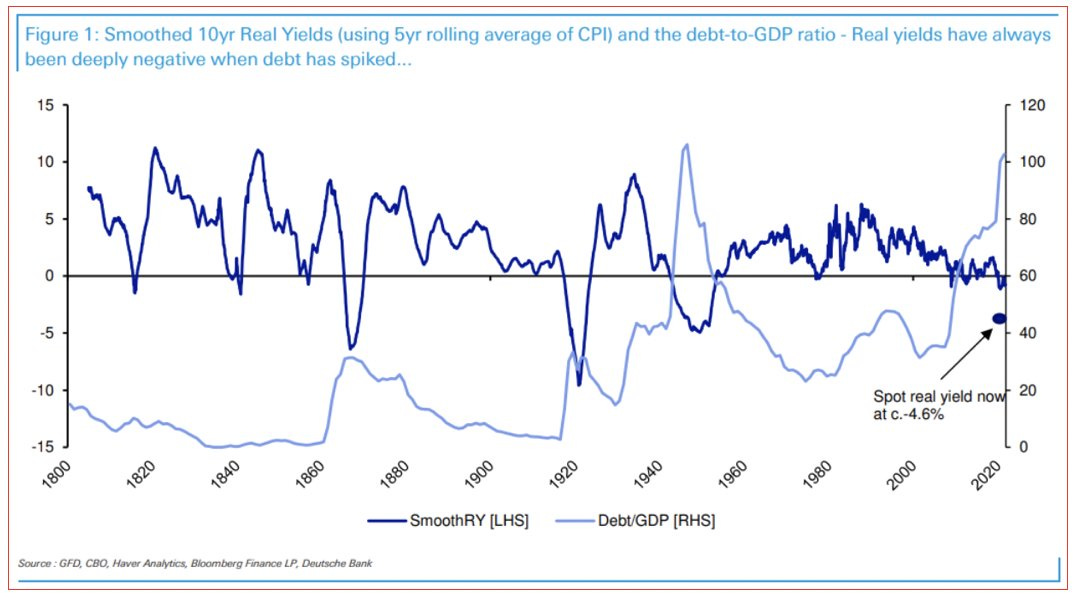

For that reason, I believe real bond yields should eventually revert to the mean. A macro thinker Steve Saretsky shared a great chart on that topic showing the evolution of the real bond yields through history (link).

So in my view, negative real yields is something that is transitory but not short-lived (wink). And while inflation will most likely decline in 2022, even with 2% sustainable inflation 10yr nominal bond yield should be above it so that bondholders are properly compensated for their investments.

Today’s US nominal 10y bond yield is 1.64%, which is -0.36% when adjusted for 2% inflation.

Higher bond yields will bankrupt the developed world

That point is often mentioned in relation to higher rates along with the Debt-to-GDP levels stat.

While Debt-to-GDP indeed is a record high, important to understand the government portion of the debt, especially the one owned by the Central Bank.

Here is how it works. Bank of Canada prints money and buys government bonds (simplified) so we see an increase in the central bank’s balance sheet and the government’s debt at the same time.

But is it really debt? When government pays interest on the debt held by the central bank, those interest payments are partially returned back to the government.

Here is a great thread on that topic:

This is significant since the Bank of Canada owns more than 45% of all outstanding government debt(link). Concerns about government debt and balance sheet could be overblown.

Private sector debt is definitely a concern, however during the pandemic the structure of private debt was improved resulting in lower debt service ratios. Higher bond yields could be accompanied by higher incomes growth offsetting the impact of rising interest payments.

Government and Central Bank would benefit from elevated inflation

High inflation is one of the potential “solutions” to the high debt problem. It transfers wealth from creditors to debtors reducing the wealth of the former ones and increasing the wealth of the later ones.

You probably heard that “There is too much money in the system”, inflation fixes that as well since it devalues money.

It can also help to resolve wealth inequality if coupled with proper taxation and subsidies.

Central banks would prefer a little higher inflation and interest rates so they have room to maneuver during the next recession. It will also devalue their balance sheets reducing it as a share of GDP. However, their hands are currently tied with the 1-3% inflation range mandate.

The statement from Chrystia Freeland confirms for me that the government is willing to tolerate higher inflation and it’s understandable why she is saying that.

Bank of Canada is holding up for now and pretty much guarantees bringing inflation back to 2%. Their mandate is due for renewal this year so it would be interesting to watch if they add something allowing them to tolerate higher inflation like 2nd mandate related to labour market, inflation averaging, or something else.

What exactly is wrong with the statement from Chrystia Freeland?

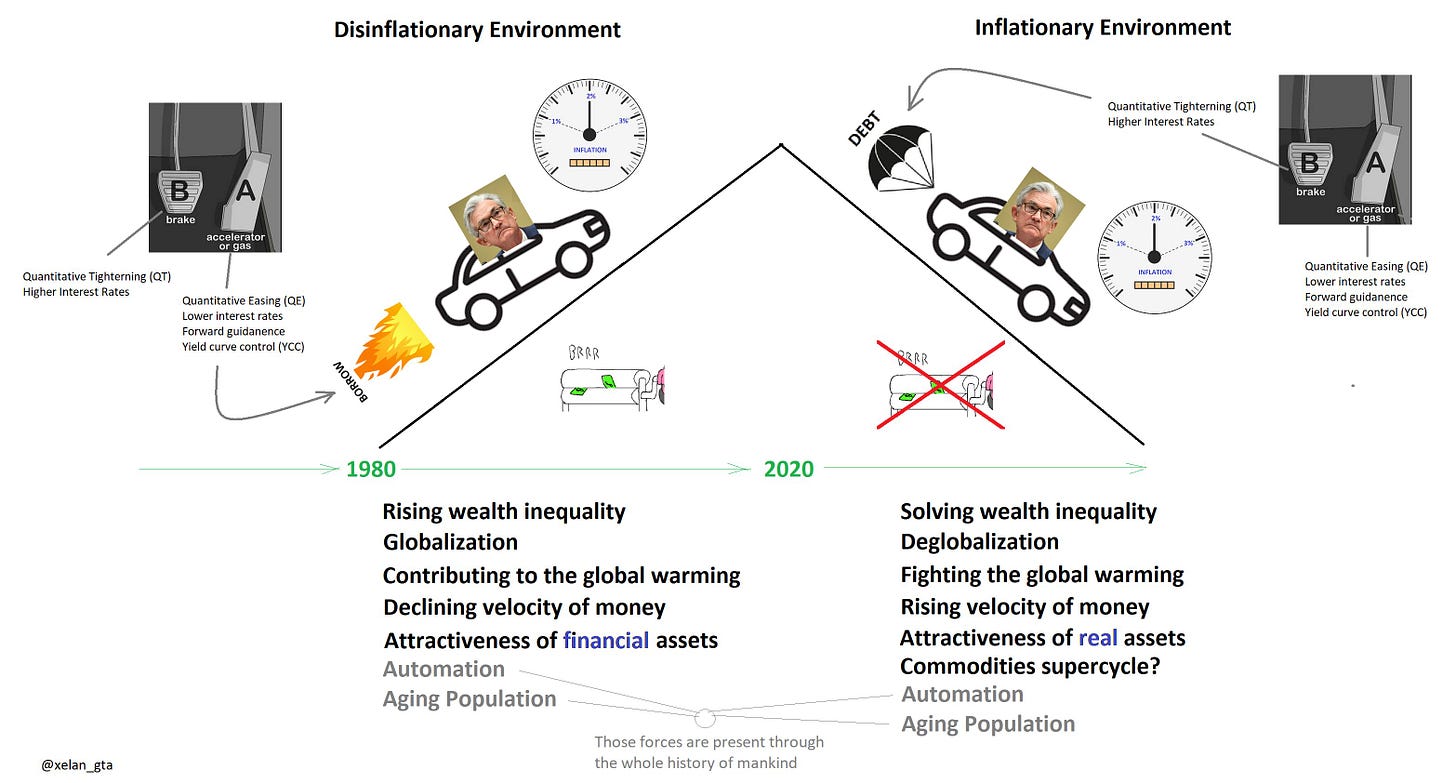

Developed world has been facing a deflationary environment for the last 40 years. Many of the factors behind it are global. One of the major ones was globalization.

However, Central Banks have a mandate to keep inflation at 2%. How would you do that in the global deflationary environment? Obviously, apply the tools you have at your disposal - drop interest rates and run QE even though those tools are very inefficient with lots of undesirable side effects.

So central bankers didn’t hesitate to apply tools domestically to offset global deflationary forces because they needed to score A+ for their inflation-targeting mandate. And hey, they did a pretty good job.

Today we are seeing global inflationary forces so if Central Bankers want to continue scoring A+ for their mandate they need to choke domestic economic growth in order to offset those forces (assuming those forces are persistent).

Chrystia Freeland made it clear they are not going to do that, however, it’s not her decision to make, all eyes are on Tiff Macklem.

Yes, it’s very inefficient to sacrifice local economic growth to deal with global inflationary pressures, so it was running QE with the hope it would boost inflation.

If Tiff Macklem follows Chrystia Freeland’s lead that would send a strong signal to the markets that commitment to keep inflation around 2% is not as strong as it was in the past.

Secular shift in inflation

There is a possibility that the world could be shifting to a secular inflationary environment. De-globalization and green initiatives, for example, are inflationary.

In one of my Twitter posts at the beginning of this year (link), I provided a sketch with sums it all up and creates an analogy with a car going uphill/downhill.

If the goal is to maintain constant speed (2% CPI) one would need to use the gas pedal more often (lower rates, QE) while driving uphill, which switches to the brake pedal (higher rates, QT) while going downhill.

In such an environment, if central banks continue to be strongly committed to the 2% inflation target they will have to intentionally choke local economic growth to meet it. If they fail to do that they are risking losing control of inflation.

This concept likely blows minds today (definitely blows Chrystia Freeland’s one) but intuitively it should be clear that if there is a time when free asset classes’ wealth is created out of thin air, there should be a time when that wealth needs to be sacrificed.

The mandate of the central bank is not to create wealth, grow the economy or prevent defaults. Their mandate is to provide price stability. It was a lucky unintended consequence that in a deflationary environment central banks overfilled the financial system with capital creating a perception that they have your back and are ready to prevent any economic pain. In reality, it was necessary to meet their 2% inflation target. I don’t believe the central bank is your friend and they will not hesitate to throw the most indebted households and businesses under the bus if it helps them to meet the 2% target in a global inflationary environment.

If they change the mandate - that would be a different story but so far that’s how I see it.

A key indicator to watch is wage growth. Without wage growth, there won’t be growth in persistent inflation. So far wages growth looks strong in the US. (not so strong in Canada)

Bondholders and savers take notes

Since inflation causes the transfer of wealth from creditors to debtors those who hold debts are financing this initiative. Savers are penalized as well by negative real interest rates.

While it’s not clear how inflation plays out from here the longer it lasts and the higher it goes - the bigger losses bondholders and savers incur.

I personally don’t think that switch in mentality after 40 years of deflationary environment will be quick, so bondholders would agree to temporary absorb the losses but if we are indeed facing a secular shift to an inflationary environment then the bond market will figure it out eventually and start to demand positive real yields for their investments.

I’m not in a position to provide any investment advice but I’m sharing many similar views with Lyn Alden and she covers investment topics. I’m not affiliated with her in any way, nor receiving any compensation, just endorsing her work.

Will we see deflation?

We might, but my perception is that deflation is the enemy number one for central banks and also governments. If any signs of deflation appear, for example, a crash in the stock market, they will flood the system again with cash as they did during the pandemic offsetting or even exceeding the impact of deflationary forces.

Another spike in inflation is more likely in my view than a deflationary episode.

That being said, there are sustainable levels of inflation of 1% and even 0%, so it’s also possible we may end up on one of those levels repeating Japan’s fate. It would be quite a depressing environment though. So far there is no indication from policymakers that an environment with lower inflation would be preferred.

Rates were similarly low after 2008 in the US, is this time different?

Rates were indeed similarly low but bond yields weren’t. I’m focusing a lot on the bond market and today’s environment is very different compared to post-2008 time. During that period bondholders were able to earn money, now they are taking losses.

Even if we ignore today’s high inflation and assume it’s going to return to 2%, the current bond yields still won’t be enough to bring real returns into positive territory.

Conclusion

The answer to the question of whether inflation is a solution or problem depends on several parameters. Combinations of those parameters will define winners and losers.

Inflation

Wages

Bond yields

Interest rates

In some cases, it may lead to deterioration of standards of living, in others it won’t. In some cases, debtors win, in others creditors. In some cases, valuations of cash-generating asset classes need to be adjusted, in others they don’t.

So it’s impossible to just label inflation “good” or “bad”, it depends.

If bond yields start to rise it will be a headwind for all cash flow generating assets since their returns are traditionally calculated as 10y bond yield + premium. At the same time, it would be a headwind for economic growth and future inflation as well.

An increase in 10y bond yield as little as 1% fundamentally could cause a correction in asset values as big as 25%.

In order to prevent that bond yields need to stay low either naturally or artificially. It’s hard to imagine yields staying low naturally with elevated persistent inflation so the central bank may choose to engage in bond yield suppression (YCC). YCC naturally works in a 0% inflation environment like Japan, but it will be very difficult to pull off with high inflation since bondholders are unlikely to accept inadequate returns and just move capital somewhere else forcing the central bank to step in and buy even more bonds. In a strong economy, it should lead to even higher inflationary pressures with little ability for monetary policy to control those. In the past, in such situations, governments stepped in and implemented various price control measures but it’s very difficult to pull off without breaking something.

If they manage to do that, high inflation coupled with low bond yields would be a very favorable environment for the debtors (including the government) leading to “inflation away” of the debts. Those who issue those debts will take losses.

Rising bond yields may not be as scary as it looks today. Part of the government interest payments on debt held by the central bank returned back to the government and there is a possibility for incomes growth to pick up strongly allowing people to service debts at higher interest rates. Declining asset values are going to improve wealth inequality (didn’t we complain about QE benefitting the rich?).

I’m sure that my views will change on this topic over time, but today that’s where I’m at.